Will they spontaneously combust if they break that magic plane just beyond your big toe? In a word; No.

Alright guys, thanks for reading!

Kidding.

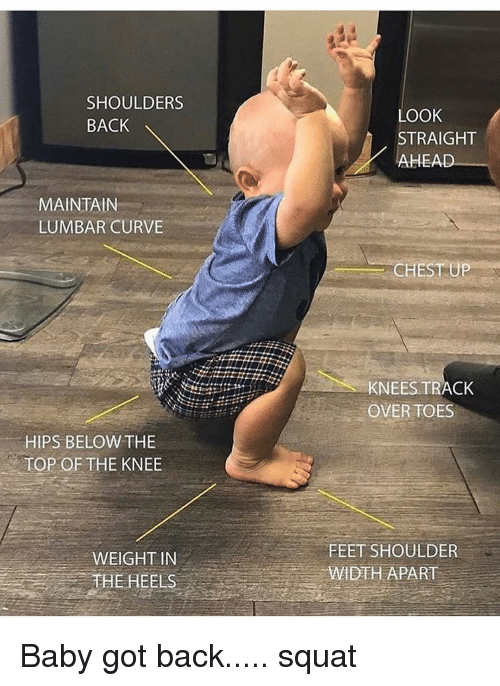

As with many other things that rehabilitative and strength fields, “it depends” is the most correct answer to the above question. I would, however, assert that MOST of the time I DO want an athlete’s knees to go over the toes whilst squatting. Or at the very least, I’d like their shins to not be “locked” at vertical. We’ll begin with a look at where the myth of “no knees over toes” came from, why I’ve gotten away from cueing that in recent years, what I cue instead, and when it may be desirable to squat with a more vertical shin bone. Let’s dive in!

“No knees over toes” likely comes from the worlds of powerlifting and rehabilitation, respectively. In powerlifting (the sport of benching, squatting, and deadlifting), keeping a more verticalized tibia may be advantageous as it has the potential to shorten the range of motion of the movement. With a shorter range of motion, the bar travels less, and one may be able to squat more weight. In regards to a powerlifting-style squat, the name of the game is to perform just enough of the motion (a squat being defined as hip crease below the level of the kneecap) to get the green light from a panel of judges before standing back up with the weight of a Honda Civic on your shoulders. Any range of motion beyond this is extraneous work and not adaptive to the task at hand. Powerlifting athletes literally train to find this range of motion (and no more!) during practice. Hence, a verticalized tibia strategy to shorten the motion may be warranted.

There’s also been a push for “no knees over toes” from the world of rehabilitation. Many folks report to Physio clinics complaining of knee pain when squatting. When asked to produce their squat, these people typically do this;

Which makes me go like this;

When a person loses her heel contact, she loses the ability to recruit hamstrings and glutes to contribute to the movement. Hammies and glutes are nice because they produce hip extension (more powerful than knee extension, vital to athletic function) in addition to stabilizing the backside of the knee joint, preventing the front side of the knee joint from slamming (legitimate medical term) into the patella. An “easy” fix to remove a person’s knee pain, then, is to tell them to keep their shins vertical when squatting. Heels stay on the ground, hammies and glutes stay recruited, and patellar compressive forces are minimized. It may look something like this;

That all sounds good, so why must I shove my knees forward when squatting? After all, the rehabilitative profession has done an amazing job of removing the pain-provoking stimulus. Champagne all around! 10 points for Gryffindor!!!

...except that what we’re left with ain’t a squat. A squat is a primitive full body human pattern that we homo sapiens use to get our center of mass as low to the ground as possible. It’s a valuable tool that we’re innately born with. It’s restorative. Rehabilitative. Prehabilitative.

It’s also a badass tool for lowering one’s center of mass rapidly.

Or performing bodily functions sans modern plumbing.

Full range of motion squatting is human. It’s an an expression of mobility of our ankles, knees, hips, pelvis, and spine. It’s rehabilitative from a life lived (and trained) in extension.

Or glued into 90 degree angles.

A well executed squat will bring a tear to any movement nerd’s eye. It tells the observer that this athlete can flex EVERYTHING in the lower body, and then reverse that motion. An athlete that can attain this position is a more robust one, regardless of sport. Incidentally, a larger range of motion will promote a greater endocrine response (HGH, testosterone), something that may be of interest to runners as these hormones are directly responsible for how well we recover from our (running) training load.

How, then, do I go about cueing a squat? “Shin bone straight” and “no knees over toes” have been replaced with “weight stays in the midfoot” and “shove your knees forward”. Keeping the weight in the midfoot ensures the heels stay down, enabling the athlete to utilize hammies and glutes to extend the hip and stabilize the knee. Shoving the knees forward allows the hamstrings to facilitate in “tucking” the pelvis, enabling full hip flexion (and subsequently ankle and knee flexion). Conversely, freezing the shin bone at vertical ensures that no motion of the ankle occurs, and the athlete runs out of room at the hip joint, potentially encouraging excessive motion from the low back.

This is one of the big reasons why I love goblet squats to teach novice athletes an effective squatting pattern. The front-placed load allows them to “sit back” to keep their feet on the ground as they shove their knees forward and get their pelvis down towards the ground.

This strategy is in rather direct opposition to an ultra wide low-bar back squat to a high box, something commonly practiced in powerlifting gyms.

From a goblet squat we can progress to a front squat if increased loading is desired. As I don’t (currently) train any powerlifters, this is typically our terminal squat progression. The addition of solid shoes with an elevated heel (olympic weightlifting shoes) let people get freaky strong in this lift while maintaining good position.

When, then, might a verticalized tibia be warranted? We already mentioned one case, that of the competitive squatter (powerlifter). The other case would be during a course of rehabilitation from an active injury or surgery. If an athlete is 4 months post op from an ACL reconstruction, I may give him a more hip dominant strategy with reduced range of motion to respect the tissue healing timeframes he’s under. This may be one case where we might use some more “powerlifting style” back squatting for a few months. However, as he heals, I’d slowly be progressing towards more range of motion and more “knees forward” with his squatting. This is where I love to use variations like a heartbeat squat to encourage gradual adaptation to the position;

In summary;

Feet stay flat and knees shove forward when squatting

A vertical tibia may make sense if your sport is squatting

A full range of motion squat is a natural, full body activity that is restorative to the ankles, knees, hips, and spine

It can, and should, recruit hamstrings and glutes in addition to quads

I use a progression from goblet squat to barbell front squat with most of my athletes

Like the content? Vehemently disagree? Share or comment below.

Looking to work with a movement and rehabilitative professional to start strength training OR take your training to the next level? Drop me a line via the “Contact” tab.